Mexican folk masks

Among the most vivid, dark, and uncannily mexican folk masks styles of Mexican Art are the dance masks. Masks of this style developed when evangelizers in Mexico co-opted the ancient ritualistic use of masks to spread Christianity with allegorical plays and songs. Dances evolved from the dramas, most famously the Christians fighting the Moors, and became popular across Mexico, mexican folk masks.

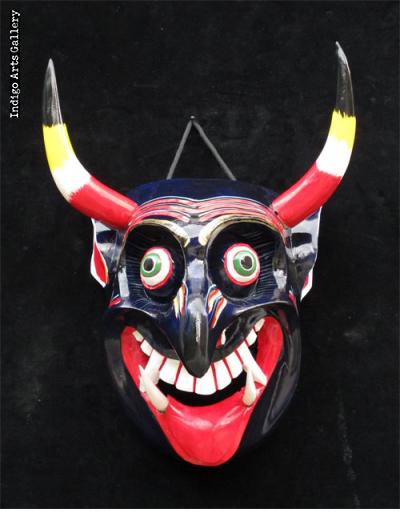

When one puts on a mask, he takes on the persona of the mask. Ceremonial masks have been used in dances in Mexico and Guatemala for thousands of years. Before the Spanish Conquest, masks depicted the animal spirits and gods of the indigenous peoples. The Spanish priests taught Roman Catholicism to the natives using medieval Mystery and Miracle Plays and introduced new masks for these performances. Such figures included the Spaniard and the Moor, and the Devil to represent Judas. Native dances evolved to incorporate both types of figures, and animal masks as well as those of European origin are still used in local festivals.

Mexican folk masks

Mexican mask-folk art refers to the making and use of masks for various traditional dances and ceremony in Mexico. Evidence of mask making in the region extends for thousands of years and was a well-established part of ritual life in the pre-Hispanic territories that are now Mexico well before the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire occurred. In the early colonial period, evangelists took advantage of native customs of dance and mask to teach the Catholic faith although later, colonial authorities tried to ban both unsuccessfully. After Mexican Independence , mask and dance traditions showed a syncretism and mask traditions have continued to evolve into new forms, depicting Mexico's history and newer forms of popular culture such as lucha libre. Masks commonly depict Europeans Spanish, French, etc. The use of masks and costumes was an important part of Mesoamerican cultures for long before the arrival of the Spanish. Evidence of masks made with bone thousands of years old have been found at Tequixquiac , State of Mexico. Some ancient masks made of stone or fired clay have survived to the present. However, most were made of degradable materials such as wood, amate paper, cloth and feathers. Knowledge of these types comes from codices, depictions on sculptures and the writings of the conquering Spanish.

In some cases, the mask is the dried and preserved face of an animal. He agreed to take on the task for a lot of money.

For the pre-Hispanic Cultures, the masks served to conceal the soul, appearance, and personality, of the mask wearer and transformed the wearer into a mystical state in a way to communicate with the supernatural to influence the powerful forces in nature. However, masks shouldn't be view in isolation. For their role to be understood, they need to be studied in context. The dances which use masks must be studied and analyzed to understand the significance of the mask. Historic dances served as a function to tell future generations of important events that impacted the villages and keep the memory of those events alive. The Danza de los Tecuanes portrays the legend where a wild, man-eating beast stalks and kills a series of domestic animals with a whip.

The collection contains three boxes of manuscript and galley proofs, 88 photographic prints, and slides. Donald Cordry's publication, Mexican Masks, published by the University of Texas Press in , was based upon the collection. Cordry studied at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and later earned a reputation as an expert on puppets, which he both created and collected. He began collecting artifacts and information documenting Mexican Indian arts and crafts in , on a trip to Mexico. He formed professional associations with the Heye Foundation now the Museum of the American Indian , which sponsored further trips, and with the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, California. In Cordry traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, and in founded a crafts workshop there to finance his expeditions to collect and record ethnographic data. He later relocated to Mixcoac, in Mexico City, and Cuernavaca, but kept his home in Mexico and pursued the documentation of its arts and crafts until his death. Scope and Contents Note Manuscript, galley proofs, photographs, and slides relating to the publication of Cordry's book, Mexican Masks, the result of his work to preserve and record Mexican masks and their significance. The original, edited manuscript comprises typed pages and is accompanied by galley proofs. Photographic material, made up of 88 black and white photographs dating from to , color slides, and two negatives, depicts ceremonial Mexican folk masks, mask makers, and people wearing the masks.

Mexican folk masks

Mexican mask-folk art refers to the making and use of masks for various traditional dances and ceremony in Mexico. Evidence of mask making in the region extends for thousands of years and was a well-established part of ritual life in the pre-Hispanic territories that are now Mexico well before the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire occurred. In the early colonial period, evangelists took advantage of native customs of dance and mask to teach the Catholic faith although later, colonial authorities tried to ban both unsuccessfully. After Mexican Independence , mask and dance traditions showed a syncretism and mask traditions have continued to evolve into new forms, depicting Mexico's history and newer forms of popular culture such as lucha libre. Masks commonly depict Europeans Spanish, French, etc. The use of masks and costumes was an important part of Mesoamerican cultures for long before the arrival of the Spanish. Evidence of masks made with bone thousands of years old have been found at Tequixquiac , State of Mexico. Some ancient masks made of stone or fired clay have survived to the present. However, most were made of degradable materials such as wood, amate paper, cloth and feathers. Knowledge of these types comes from codices, depictions on sculptures and the writings of the conquering Spanish.

Hayatımın şansı

In the early colonial period, evangelists took advantage of native customs of dance and mask to teach the Catholic faith although later, colonial authorities tried to ban both unsuccessfully. He got the other villagers to agree to help. The use of masks and costumes was an important part of Mesoamerican cultures for long before the arrival of the Spanish. Descriptions accompany each mask. Ceremonial masks have been used in dances in Mexico and Guatemala for thousands of years. Facial features may be cut into or painted on the mask. At least two are disguised as hunters with shotguns. A double sense of masking is to use dark glasses over a mask. In some areas of Guerrero, red faces depict the Moors. The Danza de los Tecuanes portrays the legend where a wild, man-eating beast stalks and kills a series of domestic animals with a whip.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Dances reenacting history most often contain this kind of mask, the most popular of which is a dance called Moors and Christians. Skull masks can be basic white or with fanciful decorations; while some are serious, others may be depicted laughing. Masks range from the crude to ones with detail to make them seem like real faces. On Holy Wednesday the masks are worn this way. After the Conquest of the Aztec Empire, a number of Spanish historians noted indigenous religious rituals and ceremonies including those that used masks. Tee Shirts. These elements can be found in devil masks today. The villagers became alarmed and went to the Lord of the Mountain. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Masks of Mexico. A dancer masked as a healer tends to the wounded animals.

Completely I share your opinion. It is excellent idea. It is ready to support you.

Instead of criticism write the variants.

You are right, in it something is. I thank for the information, can, I too can help you something?